Habits have a powerful hold on us. Many times every day we are drawn into automatic habit mode. Acting without making conscious decisions can be a good thing when we are quickly folding the laundry or doing a blitz clean-up of the kitchen before work or after dinner.

On the other hand, if we have an irresistible urge to eat cookies when we feel anxious, that may be an automatic habit that we are not pleased to have.

In The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business, investigative reporter Charles Duhigg gives us the benefit of his extensive research about the science behind the formation of habits, why it’s so hard to break a bad habit, but how we can, nevertheless, change.

Think like Safeway

The Power of Habit is a book I have returned to more than once over the last couple of years, and it’s a book I have given as a gift. It is also still on the New York Times nonfiction paperback best-seller list.

The same week that I first read the book, the Safeway Grocery Store chain launched a program that would change my habits of grocery shopping, and maybe not for the better.

I was asked at my local Safeway if I would like to have my loyalty card upgraded so that special sales could be loaded on my card. Like most people, via my loyalty cards, I had long ago handed over to grocery stores and drugstores mundane info about my purchases.

When I got home I received an email saying that sale prices just for me had been loaded on my loyalty card. Along with those personal sales, there was an additional long listing of other savings I could add to my card. All I had to do was to add the products to my card and then use my loyalty card when I shopped.

Within days, I found that this very long grocery list of discounts, just for me, grabbed more of my attention than I had ever given to buying groceries in the past. I had never paid much attention to coupons—I just bought what was on sale once I was shopping, but now I was frequently checking my personal Safeway website to see what new personalized items had been added.

Soon after that, the New York Times reported on this very same personalization program at Safeway.

Some people were quoted that they found the “big brother” aspect of the program to be “way too creepy.”

Safeway’s reward of discounts on the products I liked most, discounts just for me, had created a craving for the reward and, thus, showed me how people who mean business and throw everything at you create a process that almost inevitably becomes a habit for the target.

Julio and His Cravings

Duhigg explains how in the 1980s Wolfram Shultz at the University of Cambridge discovered how through repetition a specific reward (a bit of blackberry juice) can drive an experimental subject (Julio, a monkey) to anticipate the reward as soon as he saw the work he had to do to get the juice.

Pictures on a screen cued Julio to expect–and crave–his reward, even before he had done the necessary work of pulling a lever. Duhigg says that the research discovered by Shultz and other researchers “explains why habits are so powerful: They create neurological cravings.”

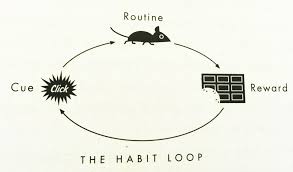

Duhigg explains how research in an MIT lab was developed to show the formation of a habit. He says that a habit is locked in through a three-step loop: “First, there is a cue, a trigger that tells your brain to go into automatic mode and which habit to use. Then there is the routine, which can be physical or mental or emotional. Finally, there is a reward, which helps your brain figure out if this particular loop is worth remembering for the future.”

Cue/routine/reward

Marketers (and Safeway) know how to make you crave a taste or a feeling and then act on that craving. How can we, as writers, use the same research to help us engage with our writing? You need to create a cue that triggers a craving to write, a craving that would help you form a habit by calling you back over and over to the writing.

Start with the reward

Finishing your dissertation and getting it off your back once and for all would indeed be a huge reward for all that work. But day-to-day, you need a cue and a reward that keep you engaging in the routine of writing.

A similar situation might be one you have met during a weight-loss program. You may know that if you keep with the program, in a few weeks or months you should reach your goal. But the real motivation to keep going day-to-day is seeing the numbers change every few days when you weigh yourself. The change seen on the scales creates a craving to repeat the process, or loop.

How could the same process work for creating text? Meeting a measurable, daily goal could function as the reward for putting in the time and effort to produce text.

For many people, few rewards/goals are more compelling than a goal of how many words or how many pages you will write that day.

Recently I challenged a dissertation coaching client who had been researching and taking notes to shift into composing her argument that would then control the direction of her writing. She agreed that she would take on that challenge, but before she did that, she wanted to finish the note-taking on the book she was reading in order to hit the 10,000-word goal she had for her note-taking. The word count was compelling to her.

She needed to replace the routine of reading and taking notes with a new routine of constructing an argument. To make use of a goal or reward that worked for her, she would still have a number to keep track of, and so we brainstormed the various types of count that would appeal to her—a word count or a page count or even a sentence count. She experimented with different rewards until she found the one that clicked with her.

Once she had decided on the replacement reward, she thought about the cue that will cause the routine to kick in. Duhigg says that almost all habitual cues fit into one of the following:

1. Location

2. Time

3. Emotional state

4. Other people

5. Immediately preceding action

My client kept the location of a particular coffee shop as the cue to start writing and working toward her reward or goal

The real Power of Habit

In The Power of Habit Duhigg says, “The real power of habit” is “the insight that your habits are what you choose them to be.” It is up to each person to choose the habits that will work for you and give you the success you want with your writing.

The science of habit formation is well documented. The habit loop is a framework that marketers have used successfully to get you to buy a specific product. How could you use the habit loop to make headway on your work? I would love to hear from you.

All the best,

Nancy

Nancy Whichard, Ph.D., PCC

Your International Dissertation Coach and Academic Career Coach

www.nancywhichard.com

nancy @ nancywhichard.com